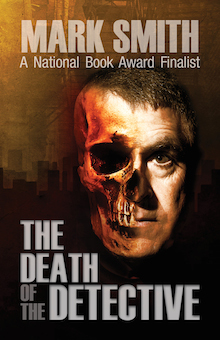

Today is pub-day for our re-release of Mark Smith’s The Death of the Detective , a National Book Award finalist and widely regarded as perhaps the best crime novel ever written. Author Ed Gorman, founder of Mystery Scene Magazine, took this opportunity to interview Mark. Here’s their talk.

It’s got to be hard to top what many consider to be an American classic. What are you working on now?

I have just finished a 168,000 word novel entitled Da Gama’s Gold (a line from Robert Frost’s “America Is Hard to See”), a reworking and reduction from a longer novel I spent too many years writing. It’s likely my most ambitious work since The Death of the Detective, and whereas that novel took on American violence, this novel explores American greed, featuring an entrepreneur con-man in place of the detective. The catalyst for the novel is the disappearance of said entrepreneur. He appears to have been a one-man successful crime ring in the mode of Doctor Mabuse, his vast crime, corruption and business world tentacles revealed as his past is uncovered. His character, which he appears to have himself created, is recreated anew by the parties seeking him out, including, eventually, crime show television. The novel has many characters and points-of-view, and is set in New England, New York, Wisconsin, San Diego, Canyon de Chelly, Chihuahua, Luxemburg and the Greek Islands.

Some years ago I decided to write a detective series, and determined I would write three books, to prove that I could do it before I sought publication. After I had barely finished the third book I lit into a fourth only to set it aside to rewrite Da Gama’s Gold. These detective novels are meant to respect the conventions of the genre, but to go beyond them by sustaining a consistent world of naturalism. Although the series features the same colorful and somewhat suspect detective– each book has a different setting and a different narrator. One book is set in rural Michigan where, after the funeral of young woman college student killed in a car crash, her boyfriend vanishes, another on a Maine island from which a young woman artist disappears, and a third in Florida and New Hampshire where a woman disappears from a White Mountains sporting goods emporium. The narrator of the first is a young discharged army officer, of the second, a woman novelist, and of the third, a writer of non-fiction books. In some cases, these narrators become detectives themselves. So far, the main characters are not so much the detective as are his narrators, or another character the narrator encounters in the story’s telling. All the novels have shocking and, I trust, convincing denouements.

I am presently at a point where I must decide between culling and reworking a second novel from the original manuscript of Da Gama’s Gold, or returning to finish the fourth detective novel. Right now I am making the finaI minor revisions to the three detective novels already written. I have spent a good deal of time writing poetry in the past decade, but am determined, at this time, to concentrate on prose.

Tell us about The Death of the Detective, a book that has garnered enormous acclaim:

The Death of the Detective is not exactly a novel in the detective genre, although it does employ, celebrate and satirize the genre’s conventions. A ‘quest’ novel in the vein of Don Quixote, Moby Dick and Dead Souls, it probably also owes something to Chaucer’s “Pardoner’s Tale.” However, it is not a white whale, dead peasants, chivalric deeds much less the Holy Grail, that the hero seeks but a maddened killer loose on the streets of what is now referred to as ‘Chicagoland’. Ironically it is the detective’s pursuit of the murderer that brings about his crimes. Along with other happenings and discoveries.

The two literary genres created in America are said to be the detective novel and the western. The detective inhabits an enclosed urban environment, the cowboy’s realm is western expansion and open spaces. Both genres feature violence. (We’re getting very American here). The character for my metaphor of the American psyche is the detective, and the setting of course, the city. The novel has a major plot and two minor plots that at times intersect, with one of the plots focused on a group of gangsters. It also has many characters and points of view and, unlike the genre, is character driven as well as plot, or story, driven. It is also very much a novel of place and period along with atmosphere and mood.

My late editor, Harvey Ginsburg, thought The Death of the Detective received the best reviews of any book he had come across. Recently when I looked up the reviews for its publication with Brash Books, I re-discovered that myself and novel had been paired, in some manner, with Virgil, Dickens, Dreiser, Bellow, Algren, Thomas Pynchon, Richard Wright, James T. Farrell, Celine, Joyce, Hogarth, Bosch, Breughal, Dostoievsky, Gorki, Hugo, Hammett, Chandler, Kafka, Gaddis, Van Eyck, Poe, Carl Sandburg and Thomas Wolf, some of them more than once. How can I explain such an impossible book? And why no composer? Was there no music on those pages?

What is the greatest pleasure of a writing career?

Besides the obvious fond moments of a first book publication, first paperback best seller, grants to write fill-time, the security of tenure in the university as an anecdote to not making enough money writing to support oneself, etc., has been the pleasure of seeing my students publish and to do well in their careers and to have met a number of fellow writers whom I have liked and respected. Before the publication of my first novel,Toyland, I received one of the first Rockefeller Foundation grants. and two years later was invited to sit on its awards committee along with Saul Bellow and Robert Penn Warren among other venerables. The air was never again as heady. These days, my greatest pleasure echoes that of the much-married swing clarinetist, Artie Shaw. After retiring at a youthful age at the height of his career as a bandleader and movie star to write apparently unpublishable short stories for the rest of his days, which were many, he claimed there was no better life to be had than to awake each morning and revise what you had written the day before. In the past decade this delight has for me included poetry as well as prose. Very soon my pleasure will come from somewhat revising the five novels that are scheduled to be published as e-books this year, four with Foreverland Press.

What is the greatest displeasure?

At times finding oneself a public person in the world of teaching and readings when the writer is a private person who prefers a lonely work place and a connection with the public on the silent and faceless page. Not that I haven’t received satisfaction from teaching. Also, disappointing is the lack of acknowledgement, never mind thanks, from some of my fellow writers for the encouragement and support given. Understandably I am sorely disappointed that I can’t read the works of Raymond Chandler and Dorothy Sayers again for the first time.

What’s your one piece of advice for the publishing world:

Better editing at all levels.

Name two or three forgotten mystery writers I would like to see in print again:

All the true crime writings of Edmund Pearson and William Roughshead. Along with the classic British detective novels published between the wars of Freeman Wills Croft, an early favorite of mine. Also, the Notable British Trial series.