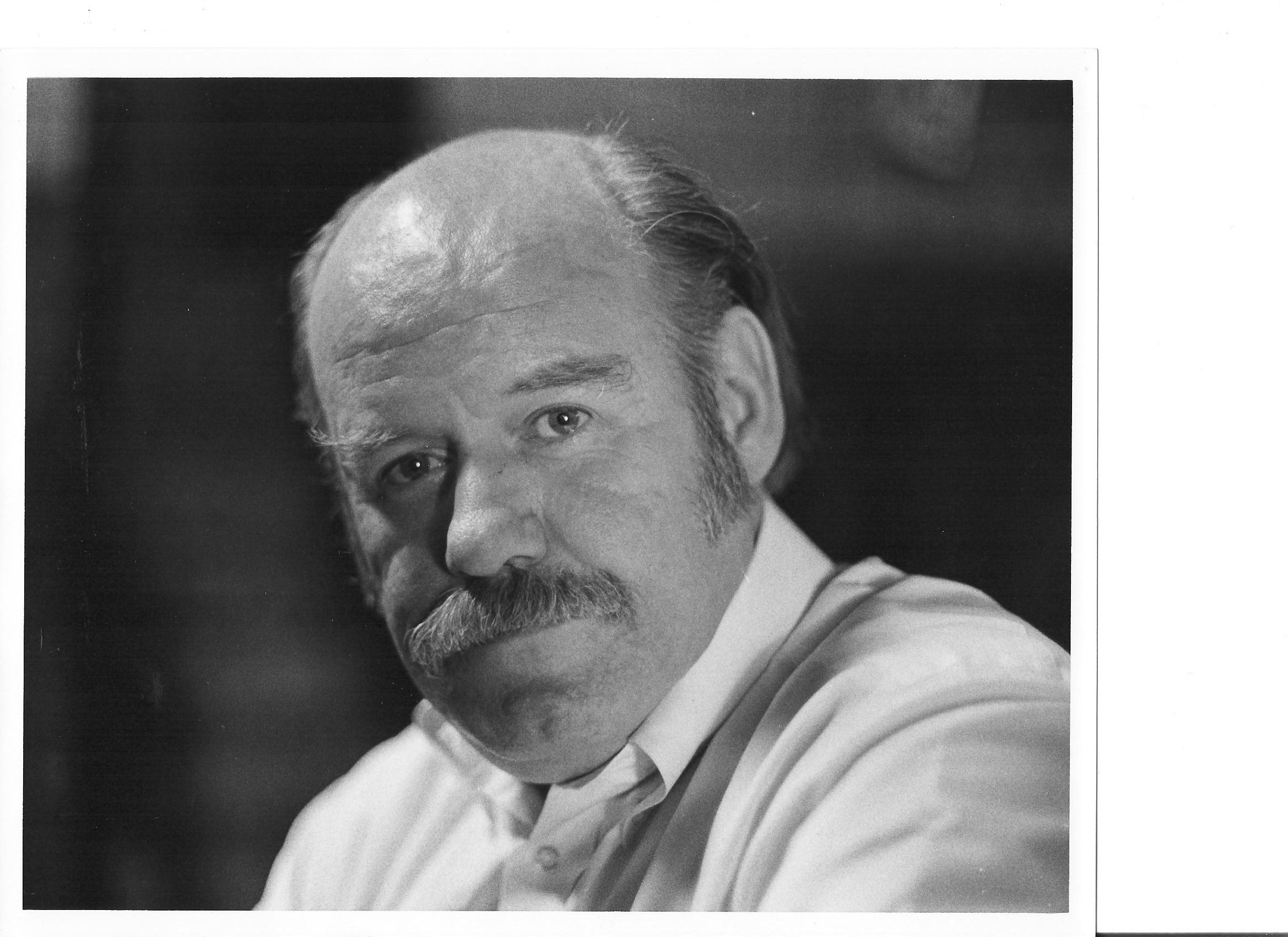

Today we’re publishing The Buy Back Blues, the 12th and final book in the Hardman series by Ralph Dennis. To mark the occasion, we’re sharing the revealing, deeply personal essay that author Cynthia Williams wrote about Ralph as an afterword for Murder is Not an Odd Job, the 6th book in the series.

I knew Ralph Dennis first as a teacher, and later as a friend and mentor. Eventually, he asked me to marry him, but I refused, and our friendship ended.

Obviously, I will remember Ralph differently from the men who knew him, because he was, in some ways, a different person with me.

I met Ralph Dennis in 1966. I was in my junior year at UNC- Chapel Hill, majoring in Radio, Television and Motion Picture Production (RTVMP), and as my rather vague intent was to become a screenwriter for motion pictures, I took Mr. Dennis’s screenplay writing classes. He was a good teacher, because I still remember the mechanics of writing a film script, yet all I remember of the classes is Ralph sitting on the edge of his desk, coffee cup in one hand and a cigarette in the other, his face expression- less, occasionally flicking cigarette ash at an ashtray. In retrospect, I suspect he may have been bored. Possibly hung over.

I liked him. He was cool. I saw him as a Hemingway-esque kind of writer. Undoubtedly, he did, too.

After I graduated in 1968, some circumstance I don’t recall brought me back to Chapel Hill while Ralph was still teaching. I remember only that we met in his hangout, a small bar on the downslope of west Franklin Street. Ralph sat across the booth from me and my young husband, clearly uncomfortable.

I intuited that I should not have brought Dewey with me. I came away from the meeting with an inexplicable sense of dissatisfaction, the feeling that I had embarrassed the man—or worse, bored him.

Four or five years later, in 1974, I was divorced, living in east- central Tennessee, and working on my first novel. By this time, Ralph had left UNC and was living some 200 miles away from me in Atlanta, trying to make it as a self-supporting writer. I have no idea how I knew where he was, unless we had kept up some kind of occasional correspondence. So many links are missing from my recollections of this time that I can scarcely connect the dots between one event and the next. Not that it matters. All I know is that over the next two years, I drove down to Atlanta a few times to spend a weekend carousing with Ralph and friends of his (including that insanely funny Ben Jones) at George’s Deli.

I recall his apartment as being one large room above a garage. As you walked in, his writing desk was to your right. To your left was a small bathroom. Beyond that, to the left, a book case and against the far wall a single-size bed. There must have been some kind of cooking facility and a table because on the one occasion I visited him there, he made shrimp scampi for me—shrimp sautéed in butter with scallions—served with a cold white wine.

I must have brought my unfinished manuscript with me that day, because I remember sitting on the edge of his bed while he sat at his desk reading it. I dared not even look at him while he read.

Finally, he stirred. I put my face in my hands as he got up with the manuscript in his hand and walked across the room to me. He stood over me with his gentle smile. “Lady,” he said, “this is a hardback.”

We walked in the park across the street one brisk, bright, golden autumn day. Ralph was rather stiffly polite, so I think it was probably during my first visit to him there. In my company, he was always a gentleman. Kind. Gentle. Smiling. Perhaps in deference to my youth and obvious naiveté. I was intelligent and well-educated, but when it came to knowing men, I was dumb as a post.

I was beautiful, you see, with a voluptuous body of which I was oblivious. I was entirely cerebral, impassioned with the life of the intellect. In my eyes, Ralph was still my teacher. He was sending me the books he said were required reading if I seriously wanted to learn how to write. The first book he sent me was Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot. Told me to read it every year, as he did. He introduced me to Turgenev with A Sportsman’s Sketches. All of the titles on his reading list were classics, heavy, rich literature. I wallowed in them with such pleasure, with an insatiable appetite for learning. And I was excited by his interest in me as a writer.

The seduction he practiced upon me was patient. Patiently, over a cheesy French onion soup with a bottle of strong, raw Chianti, he listened, smiling, to my passionate opinions about God-knows-what-all. When he spoke, always quietly and deliberately, I was an eager listener. He must have been encouraged by the warm light in my eyes, unsuspecting that it was the glow of admiration, perhaps affection, but not desire.

Every morning while our friendship lasted, he wrote a letter to me. Called it his ten-finger exercise—a warm-up for the day’s writing. I have none of the letters he wrote to me, and of them, I recall only one; he described a recent date involving “one of those sweaty, candlelight suppers” that Southern women insisted upon.

Ralph was a disciplined writer and he had to be, because his income from the Hardman books depended on the quantity of his output. He was clearly embarrassed to be writing for money, restless and angry at the necessity of it, hoping to make enough from the Hardman books to support himself while he wrote some serious hardbacks. He described his life as being a routine of writing by day and drinking beer at George’s by night.

Ralph sent me copies of all the Hardman books with affectionate inscriptions, but like the Valentine’s Day gift of The Romantic Egoists, a wonderfully illustrated, coffee table biography of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, I let them go with the rest of my library, which I sold in 2011.

The man was a hopeless romantic. He called me one day while I was visiting my brother and his wife in Asheville. Said, “Listen to this,” put the phone receiver down by his stereo and left it there all the way through Carmina Burana. Like the literature he shared with me, it was glorious. We were both mind-swerving drunk on it.

The man was a hopeless romantic. He called me one day while I was visiting my brother and his wife in Asheville. Said, “Listen to this,” put the phone receiver down by his stereo and left it there all the way through Carmina Burana. Like the literature he shared with me, it was glorious. We were both mind-swerving drunk on it.

I was enormously flattered by his attention, by the obvious fact that he had fallen in love with me. I was 28 and writers were my heroes and he was a writer. Again, I lived in my head, and again, for a young woman my age, and a divorcée, no less, I was unbelievably stupid about men. I had no sexual interest in Ralph Dennis, so I ignored his in me. For a long time, he had the good sense, apparently, not to attempt to pressure me into a sexual relationship. As I say, the seduction he practiced upon me was subtle and patient.

Unless his reticence with me was reluctance. He was a balding man with a beer belly in love with a beautiful young thing nearly half his age. He may simply have dreaded my response to any overt demonstration of sexual desire. So, he bided his time. What he had going for him, and he knew it, was my admiration for his intellect, his self-confidence and skill as a writer.

His Christmas gift to me in 1975 was a solid gold pocket watch with an inscription dated 1906. The watch was slender, as if designed to rest in the palm of a lady’s hand. It was exquisite and adored it. But I remember that, as I sat alone by my Christmas tree one night, turning the golden wafer of a timepiece this way and that to reflect the colored lights on the tree, I felt inexpressibly sad. The gift was expensive and fairly radiated Ralph’s love for me, and I knew that I did not love him the way he wanted me to and that I should not accept the gift. It was his very declaration of love. I gazed at it ticking softly in the palm of my hand, shimmering.

In hindsight, I realize that, with the gift of the watch, our relationship shifted. Ralph became supplicant.

I think it was a couple of months later that Ralph took me to an expensive restaurant in downtown Atlanta and ordered a large plate of oysters oreganata for each of us. I was embarrassed to have to admit that I could not eat oysters (they looked like phlegm on the half shell to me). Ever the compliant gentleman, he ordered me something else and when we left the restaurant, handed the carry-out box of oysters to a homeless man outside the restaurant.

Why in God’s name I felt I had to go shopping that afternoon for a lipstick liner I will never know, but we stepped into a department store and while I was at the cosmetic counter, he disappeared. Back outside on the sidewalk in front of the store, he pulled a jewel box from his pocket and opened it. Inside was the largest, most luscious opal (my birthstone) and diamond ring that has ever sparkled before my eyes. He offered it to me as an engagement ring.

I couldn’t take it. Although in my selfish desire for his friendship I had ignored all the signs of his having fallen in love with me, I was neither a cruel nor a dishonest young woman. I was embarrassed, so I hedged at first, saying the ring was much too expensive. He ignored that, urging me to put it on. I must have convinced him that I was not ready to marry again, because he finally went back in the store and returned it. I felt he was trying to force me, as if the extravagance and sheer richness of the gift would prove irresistible, but if he thought so, he did not know me. And although the gesture had discomforted, even irritated me, I have never forgotten the disappointment in his eyes when he closed the box and turned with it back into the store.

He was a sad man. Even in my memories of the fun times, of boozy laughter in smoke-filled bars, I remember him as being quiet, reserved, yet smiling, his eyes amused, and if shaken occasionally with chuckles, I don’t remember him participat- ing in our uproarious shouting and laughter. In hindsight, I realize that he was a lonely, middle-aged man watching kids having fun.

Behind the amusement, the sad man waited, watching, defeated. He had been defeated all his life by women who did not want him.

When I was in his apartment, I saw a framed photo of a little boy on a pony. Grinning, I asked if it were a picture of him. He nodded. I think he told me then that he had been orphaned very young. I learned only recently, in reading Ben Jones’s essay My Friend Hardman, that Ralph Dennis had siblings and that their mother had left them in an orphanage when he was six or seven years old. That he remembered watching, through the bars of a closing gate, his mother drive away.

I believe that a child abandoned by his mother will carry within himself always the expectation of rejection, that he will lack the sense of self-worth that is essential to achievement—be his goal winning the love of a woman or winning a Pulitzer. I believe that Ralph Dennis, for all his intellect and education and his skill and confidence as a writer, expected defeat. His very posture was that of a defeated man.

I believe that a child abandoned by his mother will carry within himself always the expectation of rejection, that he will lack the sense of self-worth that is essential to achievement—be his goal winning the love of a woman or winning a Pulitzer. I believe that Ralph Dennis, for all his intellect and education and his skill and confidence as a writer, expected defeat. His very posture was that of a defeated man.

I realize now that as a twenty-something, I intuited his sadness, his hopelessness; I knew that his need for me was emotional; I sensed that he wanted to marry me because he needed to own me. I had the vague idea that, if I married him, I would effectively become the prisoner of a jealous and controlling man.

I lost respect for him. I hotly resisted his attempts to hobble me. To bind me.

He’d call me on the phone, arguing his case. He wrote me long letters. Said that if I didn’t want to marry him, I could just live with him.

His need was an irritant. Like a fly touching my cheek, my shoulder, the back of my hand. Finally one day, I sat down at my electric typewriter and furiously typed a letter that stated my feelings in no uncertain terms. I remember the white hot fury with which I typed that day, the soot-black marks of the ink ribbon upon the white typing paper, and I remember a bit of the phone call I received a few days later. He said that my letter had been “hammering letter,” that it was “castrating.”

We had a heated exchange. I was shocked and contemptuous of his feeling of having been castrated by my refusal to marry him. Asserted (truthfully) that I had no idea what he was talking about, that if he thought a woman’s refusal to marry him was castrating, then he had a real problem, and so on and on, back and forth, until he said goodbye and I knew that he would never speak to me again.

And but for one short and final sentence, he never did.

A year or so later, I was in Atlanta again visiting the woman who had been one of the gang in the drunken glory days at George’s. I took a notion to go to George’s, hoping I’d catch Ralph there and that we could, I don’t know, hug like old friends again. Something like that. Who knows what the hell I wanted. Just to see him, say hey, be friends again.

I could have had no idea how deeply my rejection had cut him.

Sure enough, he was at the bar talking with another man when we came in. We took our seats at a booth. He gave no sign that he had seen us. I was fairly bouncing with excitement, so happy to see him again.

Finally, he walked over to the table. I looked up with an eager grin, and he said, “I said goodbye to you a year ago, lady.”

The coldness of his eyes stunned me, literally stopped my breath. I don’t know whether he turned and went back to the bar or walked out. I don’t remember anything after that.

I grew up eventually. Now I understand. Now I know.

And I can tell you this much: Ralph Dennis was not Hardman. Hardman was the man he wished to be.

Cynthia Williams is a professional writer whose work includes creative non-fiction, fiction, narrative history, and copy writing for television. The History Press published her Hidden History of Fort Myers in 2017, and in 2019, Random House will publish her children’s book, Me and the Sky. Cynthia has also recently completed a screenplay for an animated film titled, Happy. Cynthia lives on an island off Fort Myers, Florida.