Paul Bishop is a huge Hardman fan and in this essay, from our reissue of Pimp For The Dead, he talks about the cultural forces that shaped the creation of the series…and the market forces that doomed it to obscurity. Paul is 35-year veteran of the Los Angeles Police Department. His career included a three year tour with his department’s Anti-Terrorist Division and over twenty-five years’ experience in the investigation of sex crimes. He currently conducts law enforcement related seminars for city, state, and private agencies.

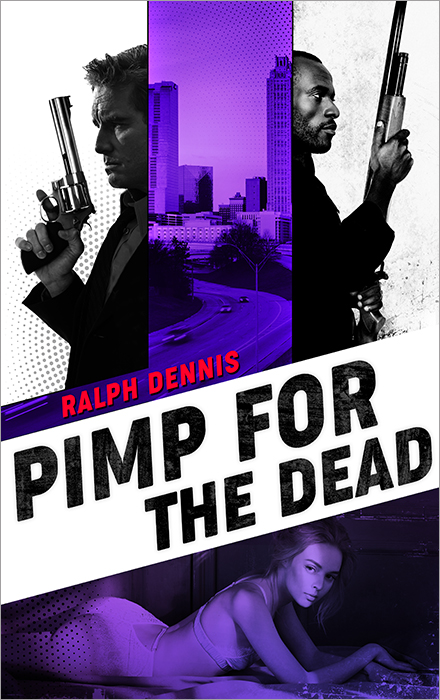

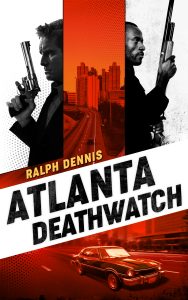

In 1974, Atlanta Deathwatch, the first Hardman novel by Ralph Dennis, debuted as a paperback original from Popular Library. It was done an immediate and deliberate disservice by its publisher, who packaged the book as a low rent rip-off of The Executioner and the other men’s adventure paperback series that were popular at the time. It was branded Hardman #1 and given a crappy cover in keeping with the standard men’s adventure genre artwork established by Pinnacle, Manor Books, Zebra and other paperback original publishers (while this is true, there is something so bad about the original covers that they have become retro-cool and collectable).

But the Hardman series was different. It was closer in quality, tone, and style to Ed McBain’s 87thPrecinct books. It had little in common with The Destroyer, The Penetrator, and other paperback vigilantes. Hardman’s closest contemporary was the hardboiled cop series Razoni & Jackson written by Warren Murphy (and the acknowledged inspiration for the Lethal Weapon films).

Hardman is a tough guy, but he’s also middle-aged, overweight, out of shape, and on occasion not too smart. As readers, we know there is no way we could be The Executioner, but we could be Hardman.

So why were the Hardman books packaged like The Executioner when it clearly wasn’t? To find the answer, we have to look at the Hardman books in the context of their time. And to do that, I’m going to have to drag you down a rabbit hole with me.

Here we go…

“The men’s adventure paperback series quickly established a set of clichés—Sexy large breasted women are in need of rescue everywhere. Unlimited ammunition is always available. A knife thrown by a hero at any range is instantly fatal. For supposedly being a secret art, ninjas proliferate like SDTs….”

Film and fiction have always reflected the cultural issues of the time in which they were produced. They are the pop culture prism through which we examine societal concerns. We use the images on screens and the text on pages to try out solutions, discard them, and try on another—like a bride searching for the perfect wedding dress. And like the bride, we sometimes have to settle for something that doesn’t make our butts look fat.

Being the redheaded stepchild of decades, the ‘70s is a perfect example of how this works. On the losing end of an unpopular war, the ‘70s was a dope-fueled mashup of political angst and discordant impossibilities, like peace, man. Not as original as the ’60s, and not as cool as the ’80s (when TV cops wore pastel colors and Italian loafers without socks), the ’70s were a generational placeholder.

The decade did offer a few scattered gems. There were no safe zones, cuddling clubs, or human flesh-bags looking for any reason to be offended or get mentioned on TMZ. You could eat beef and drink soda. Real men jogged. David Bowie released Diamond Dogs. Pineapple upside-down cake was a thing. And the Sex Pistols were dropped six days after signing with A&M records for being too outrageous to be kept on a leash.

But the dark side of the ‘70s outweighed even pineapple upside-down cake. Sacrificed on the altar of politics and warmongering, hardened veterans returned to the Land of the Free with shrapnel scars, bullet wounds, missing limbs, thousand yard stares, and haunting memories of their many brothers who died violently in an inhospitable Asian jungle.

They expected a hero’s welcome, or at least, a display of gratitude. What they got was the chilling confusion of being scapegoated as baby killers. While they had been fighting and dying, the ‘70s had been decoupaged with torn photos of disco, bell bottoms, leg warmers, leisure suits for men, and peace signs. Ten years after Timothy Leary chanted, turn on, tune in, and drop out, his mid-‘60s rallying cry had become a reality for the directionless ‘70s.

To rescue the decade from the Pit of Ennui, heroes were needed—heroes of the people, created by the people, for the people. As it had in another generation, film and fiction rose as Spartans to give us a testing zone where we could attempt to understand our turmoil, our angers, and our inadequacies.

To understand this phenomenon, we must digress to the end of another war. Like the ‘70s Viet Nam era vets, American fighting men coming home from WWII also had trouble fitting back into a society they didn’t recognize.

Post World War II America was supposed to revert to the idyllic values of the traditional family. Rosie the Riveter would willingly give her job back to a man, get out of the factory, put on an apron, and go back into the kitchen. Men would come back from the war unfazed by their experiences to take up the responsibility of providing for their families without missing a beat. If the American family was not restored to the pinnacle of its idealized, mythological form, how could we justify everything we sacrificed while fighting for our freedom and the freedom of our allies?

“Most of the covers on the men’s adventure magazines featured scantily clad, tiny-waisted, big breasted women being rescued from peril by muscular male heroes toting big guns, spears, knives, and other phallic symbols.”

However, much of America wasn’t buying it. We had been to the gates of Hell and beyond. We were warriors, and supporters of warriors. We had discovered our dark sides where we were selfish, driven, ambitious, strategic, and most importantly, we had discovered we were killers. To win a war on the largest scale imaginable, we had to go dark, black even, embracing the human wildness within.

But with peace came the expectation of normal. Everywhere we turned, we were being press-ganged into rigid conformity. Television, Madison Avenue, the stress of keeping up appearances, the responsibility for too many decisions in a world without orders to follow, created a human pressure cooker. There had to be an outlet for our wildness, our darkness, our pent up adrenaline, a way to understand the horror we had been through.

Movies gave us a conduit as film noir invaded cinemas everywhere. The genre pierced the pustules of our pain because the characters on the screen were visibly broken and jagged—they showed on the outside what we were feeling inside.

Film noir characters were desperate individuals gladly paving their own road to Hell rather than surrender to a lobotomized life in suburbia. There was something wrong with them, something the false sheen of domesticated bliss could not fix. War had released our demons and there was no stuffing them back in the jar.

Film noir characters were desperate individuals gladly paving their own road to Hell rather than surrender to a lobotomized life in suburbia. There was something wrong with them, something the false sheen of domesticated bliss could not fix. War had released our demons and there was no stuffing them back in the jar.

Americans knew they were supposed to want things bright and shiny, yet they flocked in droves to the movie theaters to see the dark seamy sides of life. During the war, they had lived film noir and knew it felt cool to be legitimately bad. Film noir was a drug, and the cinematic justifications of our feelings could not be produced fast enough to keep up with demand.

The follow-up to film noir’s punch to the mouth of conformity, was that bastard of genre fiction, the Men’s Adventure Magazines. During their heydays from the ’40s through the ‘50s, these slick-cover magazines catered to males with lurid true tales of adventure, of true wartime daring, exotic travel, and true attacks by wild animals of every ilk—as in Weasels Ripped My Flesh.

Most of the covers on the men’s adventure magazines featured scantily clad, tiny-waisted, big breasted women being rescued from peril by muscular male heroes toting big guns, spears, knives, and other phallic symbols. The covers also featured these same beautiful women about to be whipped, burned, fed to alligators, or sold into sexual slavery by leering Nazi officers, evil Nazi doctors, and horrendous Nazi torturers—who would eventually morph into outlaw bikers with the same twisted desires.

There was a need within us to confront such perversions—for men to know there was still a battle they could fight, still a damsel they could rescue (as they had rescued their wives, girlfriends, and families through the hell of battle). They needed a way to be an unquestioned hero, to forge an explanation for the terrors and revulsions heaped upon them in war. To feel something—anything—again.

Tawdry and salacious enough to be hidden down the sides of dad’s armchair or stacked in a dark corner of his garage, the men’s adventure magazines were a safe escape for men craving an existence beyond the world being forced upon, a world of societal expectations, disapproval, and repression.

Film and fiction provided a method to confront our fears by proxy until real solutions could catch up with society. When the public psyche was ready to move on, film noir and men’s adventure magazines disappeared from the mainstream, their mission accomplished.

“The Hardman series brought its own hyper-realistic take to the war on crime. It was new. It was brilliant. It was different.”

Fast forward to the ‘70s. Wars it appeared were not restricted to foreign soils. There was a war going on at home…a war on crime. A war we were losing—again. Our enemies were legion: Street criminals; shifty defense lawyers equipped with briefcases full of technicalities; delinquency; political and institutional corruption; the scourge of drugs; and the resurgence of organized crime—the Mafia; the Mob; the Felons of Oz—hiding behind their vast criminal empire.

After Viet Nam, we were confused, angry, and disoriented. We wanted a stiff drink and a way to jump off the spinning teacups. We needed a cause to unite us. Casting about, the tattered American spirit latched on to the war on crime, naïvely believing it was a war we could win. However, we needed somebody to show us how to fight this new battle, so we resurrected our old warriors—film and fiction—dressed them in new armor and sent them into the fray.

Film struck the first blow. Its weapons were language, adult content, sexuality, and violence—all on the big screen. The loosening of restrictions on these cinematic elements reflected the counter-culture’s embrace of free love, edgy rock-n-roll, the civil rights movement, changing gender roles and drug use. Old style Hollywood moguls were dying out and a new generation of film makers was eager to take their place. Hollywood was stretching conventional boundaries as films began to aggressively expose the dark underbelly of the times.

Fiction joined the battle bringing a game changing big gun, the ultimate in ‘70s darkness…Death Wish.

Fiction joined the battle bringing a game changing big gun, the ultimate in ‘70s darkness…Death Wish.

Brian Garfield’s 1972 novel, and the subsequent 1974 film starring Charles Bronson, spoke to the ‘70s as nothing else could. It addressed the heart of our frustration. But Death Wish was a sheep in wolf’s clothing. It was a be-careful-what-you-wish-for warning hidden (perhaps too well) beneath a savage fable of wish fulfillment and revenge.

Caught between literary and genre fiction, Death Wish destroyed the ramparts of convention and loosed the dogs of war. Led by Don Pendleton, dirty dozens of hard-bitten, cynical, fast typing genre writers charged into the breech. With his novel, The Executioner #1: The War Against the Mafia, Pendleton spawned a whole new fiction genre of men’s adventure paperback original series.

The Executioner Mack Bolan’s deadly fighting skills and fearsome reputation were forged in the hell of Viet Nam. When he returned stateside to find his family destroyed by drugs and criminals, Bolan geared up to bring the hell of war down on the Medusa head of organized crime.

The men’s adventure paperback series of the ‘70s were akin to the men’s adventure magazines of the ‘50s, but there was one big difference. The true stories in the men’s adventure magazines of the ‘50s looked (albeit salaciously)to past events. But the men’s adventure paperback series of the ‘70s looked to the present and to the future beyond.

The simple, yet spiritually patriotic theme, as established by Pendleton, of taking back the streets of America from pimps and mobsters, unleashed the imagination of a new generation of pulp writers. Uncountable men’s adventure paperback series exploded onto spinner racks in every five-&-dime, supermarket, and drugstore across the country. Clearly, the American psyche was willing to accept the war on crime could only be won by lone vigilantes rising up from the ranks of the everyman to massacre robbers, thieves, drug lords, corrupt cops, pimps, hitmen, hoods, goons, lowlifes and Mafia dons across the country.

The reading public’s appetite for the genre appeared insatiable. The Executioner, The Destroyer, The Penetrator, The Expeditor, The Inquisitor, The Liquidator, and the Protector joined the likes of The Death Merchant, The Revenger, The Killmaster, The Marksman, The Sharpshooter, and dozens of other mercenaries, reformed hitmen, and Death Wish-lite vigilantes to fight our battle.

The men’s adventure paperback series quickly established a set of clichés—Sexy large breasted women are in need of rescue everywhere. Unlimited ammunition is always available. A knife thrown by a hero at any range is instantly fatal. For supposedly being a secret art, ninjas proliferate like SDTs. The faithful, yet weak and desperate companion always saves the hero’s ass in a pinch. Explosives always go off in the nick of time. Before killing the captured hero, super villains will always explain their nefarious plot, giving the hero the chance to escape. The key to victory is courage and smart-ass remarks.

In mainstream fiction, when all is said and done, a great deal is said and very little done. In genre fiction, not much is said, but a great deal is done, which finally gets us to the bottom of the rabbit hole and to the tea party with Hardma n and Hump.

n and Hump.

The men’s adventure paperback series’ bred many similarly packaged series, each a slightly blurry version of the original mold. Other genres, Westerns in particular, sought to tart up their own genre’s standard tropes by dressing them up as men’s adventure series.

The Hardman series brought its own hyper-realistic take to the war on crime. It was new. It was brilliant. It was different.

Unfortunately, it was bought by Popular Library, which built their publishing business on knock-offs of whatever was hot at the time. Popular Library did not establish trends. Instead, they chased them, picking up the leftover genre dollars along the way.

Faced with the superior writing quality of the Hardman books, Popular Library panicked. They recognized the series was a hybrid, but they didn’t trust it to find its own niche in the market. Popular Library didn’t trust different.

Having no clue how to sell different, the publisher threw Hardman overboard to flounder in the vast sea of vigilantes and Death Wish imitators.

As the ‘70s took hold of its destiny, the men’s adventure series paperbacks fell out of favor. Some held on through the ‘80s, but eventually they too disappeared the same way film noir and men’s adventure magazines did when their cultural stress release was no longer needed.

By touting the Hardman series as something it wasn’t, the books got short shrift and quickly fell into the same obscurity as the men’s adventure genre. Hardman deserved much better.

Even in obscurity, the Hardman books continue to be something special. While the lingo and attitudes were warts of the ‘70s, the characters, their relationships, and the quality of Dennis’ writing was timeless. The series became a hidden genre gem. It was whispered about only by the most hardcore genre fans—who turned collecting the twelve sacred Hardman books into a quest of mythical proportions.

However, it appears you can’t keep a Hardman down. Once Brash Books co-founder Lee Goldberg discovered Hardman, he began a legendary quest of his own to bring the series back into the mainstream. And now he has succeeded with the publication of these new editions. Wrapped in stunning and appropriate covers, this lost literary treasure of the ‘70s is finally getting the recognition it deserves, and Jim Hardman and Hump Evans have found themselves officially added to the pantheon of hardboiled greats.

Paul Bishop is the author of fifteen novels and has written numerous scripts for episodic television and feature films. His latest book, Lie Catchers, is the first in a new series featuring top LAPD interrogators Ray Pagan and Calamity Jane Randall.