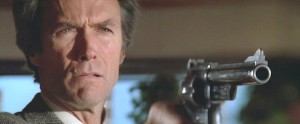

Do you feel lucky? Well, do you, punk? Because you should. You’re lucky because you’re about to get some great writing advice courtesy of Dirty Harry and Gar Anthony Haywood, the author of Man Eater and Firecracker, both published by Brash Books.

Most people think that…

“Go Ahead, Make My Day”

But I beg to differ.

Clint Eastwood has snarled a lot a memorable things over the course of the five films in which he’s played the iconic Dirty Harry (DIRTY HARRY, MAGNUM FORCE, THE ENFORCER, SUDDEN IMPACT and THE DEAD POOL), but in my opinion, as meaningful snippets of film dialogue go, his “make my day” line doesn’t hold a candle to the one he dropped, more than once, in MAGNUM FORCE:

“A man’s got to know his limitations.”

While the “man” Harry was talking about was his two-faced supervising lieutenant (played to hair-raising perfection by Hal Holbrook), his statement could have applied just as easily to writers as policemen. Because the writer who’s constantly working beyond his limitations — which is to say, outside the boundaries of his innate strengths — is probably not writing very well.

“Limitations?” you say. “I don’t believe in limitations!”

And that’s understandable, of course. Who among us wants to think that there are things we would like to write that we can’t? Things, in fact, that we may be ill-suited to ever write particularly well? Such ideas run counter to everything we’ve ever learned about the power of positive thinking and the indomitable creative spirit.

Still, I think there’s something to Dirty Harry’s declaration.

One of the most common fears we professional writers have is that an unpublished novel from out of our past will someday be discovered and published, to great critical abuse, after we’re dead. Something we’ve determined should die unborn will instead be dredged from the depths of our effects and made public the moment we’ve been lowered into the ground. It’s a terrible thought, isn’t it? And yet, I don’t happen to have this particular concern. I don’t have it because none of the dozen or so novels I attempted to write, prior to finally publishing FEAR OF THE DARK, would add up to 200 pages. FEAR OF THE DARK was the first novel-length manuscript I ever completed; all the others petered out and died after two or three chapters. (And this is a very good thing, people, believe me. They were all dreadful.)

There were many reasons for all the false starts: lack of skill, preparation and commitment chief among them. But one of the main reasons most of these novels died on the vine was that, in each case, the realization inevitably dawned on me that I was trying to write a book I was not equipped to write. It was not my book. Instead, it was a book outside my realm of competence: too big, too complex, too far removed from my particular life experience.

I loved spy novels, so I tried to write spy novels. I enjoyed comic westerns, so I tried to write a comic western. Science fiction, horror, coming-of-age melodramas — if I read it and loved it, I tried to write it, and almost always with the same disappointing result: an unreadable, unconvincing manuscript. Only when I set my sights on FEAR OF THE DARK — a classic, hardboiled private eye novel that fit right in the groove of my interests and skill set at the time — did I write and finish a book that felt like my very own.

I loved spy novels, so I tried to write spy novels. I enjoyed comic westerns, so I tried to write a comic western. Science fiction, horror, coming-of-age melodramas — if I read it and loved it, I tried to write it, and almost always with the same disappointing result: an unreadable, unconvincing manuscript. Only when I set my sights on FEAR OF THE DARK — a classic, hardboiled private eye novel that fit right in the groove of my interests and skill set at the time — did I write and finish a book that felt like my very own.

Did I do the right thing in pulling the plug on all those other manuscripts, rather than soldier on to each one’s ultimate conclusion? I think I did. I could have done a ton of research to fake my way to the very end of one or two, sure, but I don’t think that would have accomplished much, because it wasn’t just an insufficient knowledge of the material involved that made me the wrong person to be writing these particular books. It was the fact that I had little or no personalperspective on them; I was a foreigner trying to write a book only a local could really do justice to.

Write What You Know?

I know this all sounds like an argument for that tired, age-old piece of advice that says a writer should only write what he knows, but that’s not what I’m suggesting at all.

What I am suggesting is that, just because you can learn all there is to know about something and then write a book about it, that doesn’t mean you should. How well suited you are to write a given book doesn’t begin and end with how well informed you are about its subject matter. There are other qualifications to consider as well, such as:

- Insight: What insight, based upon your own personal or professional experiences, do you have into the material? Will you be writing from the inside looking out, or from the less advantageous perspective of an outsider trying to peer in?

- Passion: What reasons do you have to be passionate about this book? What makes it one you needto write, rather than one you’d simply like to write?

- Motivation: Have you decided to write this particular book because it appeals to you artistically, or are you simply chasing the dime? Would this still be your project of choice if all commercial considerations were set aside?

- Confidence: Is this a book you can write with a level of confidence the reader can actually feel? Or will your self-doubts regarding your command of the material, regardless of how much research you’ve done, be noticeable on every page?

- The Fun Quotient: Yes, writing is work, and it’s not supposed to be all fun and games, but a book that’s well-suited to your talents and interests should, on some level, be enjoyable to write. If, instead, you find writing it feels like a daily stint on the San Quentin rock pile, you may very well be writing somebody else’s novel, not yours.

What’s Your Wheelhouse?

In baseball, they call the area around the plate in which a pitched ball is most likely to be pounded by a given batter his “wheelhouse,” and I believe all writers have wheelhouses of their own. That’s where your best work lies. Over time, as you grow as a writer, your wheelhouse grows naturally right along with you, broadening the range of material you can write reasonably well. But unless you’re one of those rare genetic mutations who are capable of writing anything they choose with equal brilliance, there will always be books that reside outside your wheelhouse, and those are the ones you’d be better off leaving alone. Taking a swing at them instead — to run with my baseball metaphor just a little while longer — is more likely to earn you a strikeout than a homerun.

There’s a published author of my very casual, online acquaintance who does a great deal of crowing about the diversity of his work and his determination to write in and across all genres. It seems he’s intent on writing any book, for any market, that suits his fancy. From an artistic point of view, this sort of blind ambition may be admirable, but as a business plan, I think it’s a disaster, because it’s based upon a rather vain assumption of professional infallibility that few, if any of us, can honestly claim. Anyone less than a literary phenom, in fact, following this guy’s formula, is going to write some books that work and a lot more that don’t, and surely life is too short to be wasting time writing the latter just to flaunt one’s disdain for boundaries.

There’s a published author of my very casual, online acquaintance who does a great deal of crowing about the diversity of his work and his determination to write in and across all genres. It seems he’s intent on writing any book, for any market, that suits his fancy. From an artistic point of view, this sort of blind ambition may be admirable, but as a business plan, I think it’s a disaster, because it’s based upon a rather vain assumption of professional infallibility that few, if any of us, can honestly claim. Anyone less than a literary phenom, in fact, following this guy’s formula, is going to write some books that work and a lot more that don’t, and surely life is too short to be wasting time writing the latter just to flaunt one’s disdain for boundaries.

Let me state for the record that none of this is meant to imply that a writer shouldn’t always try to stretch himself, or make a constant effort to avoid being pigeonholed. Versatility is a wonderful thing. I am, however, suggesting that smart authors assess their strengths, weaknesses and comfort level with certain types of material, honestly and accurately, and prioritize the things they write accordingly, for their best possible chance of success.

And they don’t much care how much credit they’re given for being someone who can write anything they damn well please.

Questions for the class: Name an author you love to read, but wouldn’t dare attempt to imitate, for the reasons I’ve stated above. Or instead, make an argument for why you think no kind of book should be off-limits to you.

Gar Anthony Haywood is the two-time Shamus & Anthony Award winning author of Man Eater and Firecracker, both available from Brash Books.