Brash Books is republishing the 12 Hardman novels by Ralph Dennis…. a brilliant series of crime novels long sought-after by collectors and beloved by crime writers. Very little is known about the author, who died in 1988. So we sought out some of the people who knew him best to tell us about him. Ben Jones was one of Ralph’s oldest friends and became famous as an actor (he was “Cooter” on Dukes of Hazzard) and later as a Congressman from Georgia in the House of Representatives. His remembrance of Ralph below appears as the Afterword in the Brash edition of the Hardman novel Down Among the Jocks.

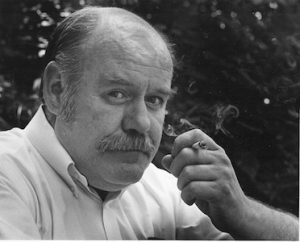

If, on a late summer afternoon in 1973, you had walked into George’s Deli on Highland Avenue in Atlanta, you would likely have seen a portly man in his 40’s. He would have been on a barstool talking to his friend Sam Najar, the bartender. The customer is balding. It is all gone on top. He has sideburns that are beginning to show grey. His round, mustachioed face is pocked, and his Falstaffian beer gut cannot help but be noticed.

He is wearing a casual white short-sleeved shirt, khaki slacks, and brown loafers. If he knows you and likes you, he will ask you to join him at a booth. If your interests run to literature, writing, pop culture, film history, good wines and liquors, Japanese and Italian food, Southern ribaldry, or the traditionally American sports like baseball, football and basketball, you will soon realize that he knows more about all of these things than you do. And then you will start listening and learning. Because this guy, Ralph Dennis, is a great teacher.

From 1961 until his passing in 1988, Ralph was my friend, my mentor and my sidekick. In a few drunken instances, it fell to me to be his bodyguard. In those 27 years we had only one falling out, over a red-headed woman as it happened, and it was entirely my fault.

We had some things in common. I had grown up in a railroad section house without electricity or indoor plumbing by a railyard on the docks of Portsmouth, Virginia. Our shack was literally on the wrong side of the tracks in segregated Sugar Hill, then a bustling African American community. We were the only “white” folks in Sugar Hill. I know of that now as one of the great blessings of my life.

After a feckless high school career, I worked a series of odd jobs and saved up enough dough to enter East Carolina College in Greenville, North Carolina. While there, I saw a pamphlet about the Radio, Television, and Motion Pictures Department (RTVMP) at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. I sent a handwritten letter to the UNC Admissions Department, and on the basis of that letter I was accepted. The Dean told me that they thought I had some writing talent.

One of the first courses I took was the survey course for RTVMP, a very large class in a vast auditorium. The graduate assistant who taught the writing section of that course was Ralph Dennis. He was very good at what he was doing, a fine and entertaining lecturer, and, though a bit droll and sardonic, he was never, ever boring. I liked his style, and related to his humor.

Most of the Chapel Hill drinking spots were clustered then on East Franklin St., directly across from the North entrance of the campus. But I had noticed a tavern some blocks west of there that piqued my interest, a place called Clarence’s. It appeared to be more of a good old fashioned working man’s beer joint.

The first time I walked in there, the only guy in there besides Clarence himself was Ralph. He seemed to be totally at home, as if he had lived there for some years.

I introduced myself. He was then 30 years old and I was 20. In that conversation and in thousands of others over the years, I learned a lot about Ralph, and a little bit about myself.

It was at Clarence’s that we first bonded over a mutual appreciation of country music, sports, and film. We poured our beer change into the jukebox and as the regulars started coming in, I matched every Budweiser he drank with a Pabst Blue Ribbon, which was a nickel cheaper. He knew that I didn’t have much dough, so he would spring for just about every other round. I realized early on that this was a sympaticorelationship. We were both devoted to that old, but elusive, romantic notion of the artist’s drinking life.

Like me, Ralph had come from a bone deep hardscrabble Southern raising. He didn’t like to talk about it, but the story emerged over our shared years of lubricated conversation. Ralph was born in 1931, as the Great Depression was sinking ever harder into the American heartland. There were scars from those times that he clearly bore, but they were sealed and protected by a cranky, crusty, and often cynical attitude.

What had gotten him away from a future in the cotton mills was a High School teacher in his hometown of Sumter, South Carolina who recognized and encouraged his gifts of intelligence and writing talent. He spoke of her often as something of a savior.

After high school, Ralph joined the United States Navy, and headed to the Korean War. The highlight for him was a beautiful Geisha girl in Japan he lived with for a year or so. The lowlight was when an angry officer ordered him to drive a jeep across an airfield to his headquarters. Ralph jumped in and drove the jeep into a series of potholes and through a fence into a ditch. The irate officer didn’t know that Ralph had never learned to drive. That fact made the officer even more furious.

“Then why in the hell did you do it?!”, he yelled.

“Just following orders, sir”, Ralph replied. “Just following orders.”

And that was the first and last time that Ralph Dennis ever took the wheel of a vehicle.

He came home from Korea and Japan and used the G.I. bill and some scholarship money to pursue his writing ambitions. At Chapel Hill, he got an A.B. and a Masters, which he was working on when we met in the early 60’s. There were some wild ass parties around there in those days, when sex, drugs, and rock and roll ruled the roost. Ralph got lucky with women now and then, didn’t do any drugs other than alcohol and Pall Malls, and liked his music more nuanced and melodic than most. He was, after all, a bit older. And though it wasn’t easy to pick up on, he was also a whole lot cooler than the folks who thought they were cool.

Ralph headed off to the Yale School of Drama for a doctorate somewhere around 1963. I got hitched to a gal from Texas and didn’t pick up with Ralph until he got back in 1966. He had gotten another Masters, but he did not leave Yale under good circumstances. My attempts to find out what had transpired would end with a grunted comment about “an enormously stupid asshole.” I understood. If nothing else, Ralph Dennis was a proud man, the kind of brilliant Southern country boy who knew what he was trying to do as a writer, and he knew how to do it. Apparently, he felt his Doctoral adviser was condescending and that the guy was trying to jack him around simply because he thought he could. Ralph told him to “put it where the moon don’t shine.”

There was also a woman up there, a very serious affair which had also ended badly. There was a lot more to it than that, but Ralph was reluctant to discuss it and I was just smart enough not to push it.

There was also a woman up there, a very serious affair which had also ended badly. There was a lot more to it than that, but Ralph was reluctant to discuss it and I was just smart enough not to push it.

But the University of North Carolina wanted him back, and he was glad to be back. His daily routine was simple. He would grind himself some good African or Brazilian Coffee, then walk to the campus from his modest apartment to teach at Swain Hall, home of the RTVMP Department. After classes, he would read and critique scripts, and when that was thoroughly finished, he would head to Jeff’s Campus Confectionery to hang out with the other regulars who held court there, myself included. We drank a lot of beer in those days. I mean a hell of a lot of beer. We drank staggeringly prodigious , Homeric, Olympian Record amounts of beer.

Jeff’s was a little newsstand with a bar in the back. There were no stools, but every day a truly diverse group of beer boozers would stand around for hours, rolling dice to see who was going to buy the next round. There were times when I’d knock off from my job waiting tables at Harry’s Deli up the street and head for Jeff’s. If I was lucky with the dice, I could drink for hours. There was an ancient bank safe in there, and it became my barstool. There was a bench in the back with a black and white 9 inch television set with extendable “rabbit ears” that someone had to hold and move around when the Tar Heel Basketball team was on.

If Ralph didn’t show for a few hours, it was likely because he was working on a short story or some other writing project. He published some in small magazines, and he was at ground zero with the novelist Russell Banks’ literary magazine, Lillabulero. I wrote a bit, and published a bit, but once I discovered I could make a little dough as an actor, I was hooked on the theatre.

I was in between marriages when I ended up in Atlanta in the fall of 1969. I got a union gig as an actor the day after I got off the bus. My Georgia girlfriend Mary Alice and I got hitched down in Briarpatch, Georgia, and we quickly found that there were a number of former Chapel Hillians in “Hotlanta”, celebrating the New South and having a grand old time doing it.

By 1970, Ralph was “getting tired of students” and needed a change. It didn’t take much to convince him that Atlanta had fully recovered from General Sherman and was a happening place. We drove up and got him and his belongings and helped him find a bachelor’s pad. He got a regular job when his savings started to dwindle a bit, all the while writing every day. He wrote to his friend and agent Elizabeth McKee, pitching the idea for Hardman. Ms. McKee secured a contract with Popular Library.

Now, I wasn’t there when it happened, but he was so overjoyed with the news that he ran the two and a half miles to our house so that he could tell somebody. Ralph Dennis had given up athletics in High School and was as out of shape as one would expect of a man who had downed 50 beers a week for 25 years, while chain-smoking Pall Malls.

But he made it. I wasn’t at home, but Mary Alice was.

“I sold a book!!” he said.

Mary Alice said he was so happy that for years afterwards she found the moment “thrilling”. And I still can’t help but smile when I think of that day.

Jim Hardman and Hump Evans were born that day. The books were excellent. They were the work of a thorough professional, working within a genre he greatly respected. Of course, Ralph had read all of Chandler and Hammett. But he seemed to have also read all of everyone else who ever put ink on paper: Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, all of the Russians, all of the Classics and all of the Americans, Twain and Faulkner and especially Hemingway, whose style of carving out anything unnecessary was not lost on Ralph.

Ralph would write a first draft in two or three days. “Get the whole thing down as soon as you can,” he told me. “The work is in the re-writing.”

He loved to polish a sentence until there wasn’t a trace of “fat” in it. He did the Hardmanbooks with the work ethic of a coal miner, staying at it until there was nothing left to add or subtract.

Those streets and alleys of 1970’s Atlanta have greatly disappeared now, paved under and over as a behemoth of a sprawling megalopolis has been birthed from the Georgia red clay; 14 lane super-highways circling through a maze of high-rise glitz and chrome. But if you know where to look… there was the Clermont Lounge… there was Plaza Drugs… there was the Stein Club… there was the “strip at Tight Squeeze”.

Ralph and I were both alcoholics, but of a different sort. When I went on a binge, I couldn’t stop until the game was over. As the old alkies say, “One drink is too many, a thousand isn’t enough.” But at a certain time in the evening, Ralph would say, “I need a lift home, I’m really ‘schnokered’,” and that would be that. I’d drop him off and go back out, looking for more trouble.

I was heading for a bad bottom in 1976. The Georgia lady had enough of my insanity and left. But the drinking got worse. I got married again, and that hardly lasted longer than the first hangover. No one wanted to see me coming down the street.

I was heading for a bad bottom in 1976. The Georgia lady had enough of my insanity and left. But the drinking got worse. I got married again, and that hardly lasted longer than the first hangover. No one wanted to see me coming down the street.

Ralph and I argued over that red-headed woman and it caused a break in our long friendship. It was entirely my fault.

He got a book deal for MacTaggart’s War (which Brash is republishing as The War Heist) and went to England on the advance to do some research. I was making good money doing movie roles and spending it with no regard for anything except to be, as Dylan Thomas said, “the drunkest man in the World!”

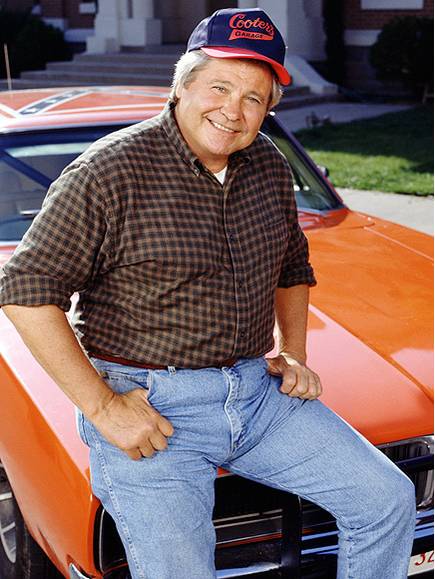

I got sober in September of 1977. It was the start of another life for me. Soon afterwards Ralph tired of the Atlanta scene and went back up to Chapel Hill to write and teach. A year later, I was cast in the mega-hit TV series, The Dukes of Hazzard. My life changed so dramatically, that it seemed an entirely different life. It was and still is.

I didn’t see Ralph for a couple of years, but we kept up through mutual friends. I sent him a letter of amends and he appreciated it. He was proud of how I had changed my ways and found some success.

After five years of sobriety and jumping cars in Hazzard County, I went up to Chapel Hill in 1982 when The Tar Heels were playing for the National Basketball Championship against Georgetown. The game was in New Orleans, but I knew the real action would be in Chapel Hill, especially if the Heels won. I went to where I knew Ralph would be, at Jeff’s Campus Confectionery. He greeted me like the long-lost brother I was. He was drinking Michelob, I was drinking Diet Coke.

The Tar Heels won on a last second shot by Michael Jordan, a skinny 19-year-old freshman. The Victory celebration on Franklin Street was beyond wild, as it should have been.

Ralph returned to Atlanta the next year and to his stool at George’s Deli. He got a job at the Oxford bookstore and kept writing. When I was in town, I’d pick up Ralph and we’d hit the Atlanta Braves or Hawks games, me drinking green tea, and him downing Budweisers.

When TheDukes of Hazzard ended in 1985, I asked Ralph to come up with an idea for an Atlanta detective series. I said that the Hardman series would make a terrific television show. He agreed, but he felt I wasn’t right to play Jim Hardman. And then he said something that seemed to come from a deeper place.

“Hardman is ‘in’.” he told me. “But you are ‘out’.” I think he was saying that I had escaped from my addictions and my despair, but that Hardman (and Ralph) had not and likely never would.

Instead, he did a half-dozen, two-page outlines of possible stories, and a full treatment for a pilot episode, for a different detective series called Gunnarson. Steve Gunnarson was a former jock and Special Forces guy who had inherited the family bookstore, which specialized in rare books and maps. The other side of “Gunnarson, the Hardass” was “Gunnarson, the thoughtful Renaissance Man.” Gunnarson “did favors” for friends with problems, a sort of dangerous hobby. I thought the time was right for an Atlanta show. (I played on a softball team there with Isaac Hayes, and we wrote a part for him.)

I pitched Gunnarson to CBS in that same endless line with everyone else in Hollywood who could “get a meeting”. Nothing happened. It rarely does out there. I think they were just being courteous.

In 1986, I was approached by the State Democratic Party to see if I was interested in running for Congress. “I’ve got more bones in my closet than the Smithsonian Institute,” I told them. But the Party was desperate. And a lot of folks, including Ralph, told me that I didn’t really have anything to lose and that I should jump in just for the hell of it. Ralph wrote my first political speech. He had never written one, and I had never given one. I almost won the race, and ran again in 1988.

George’s Deli on Highland Ave. was smack in the middle of that District and I would stop in to see Ralph whenever I had a few minutes. He was having some health problems and job problems and was crankier than ever. While Ralph was looking for a new apartment, George was letting him sleep on a cot in the back of the place. During one night, he had a seizure of some sort and was found in a coma the next morning. He was rushed to Crawford Long Hospital near death, but recovered enough to have several female visitors a couple of days later. Then it went the other way. The day before he died I spent time at his bedside with his kid sister Irma, who flew in from Michigan. He died on July 4th, 1988, as fireworks exploded everywhere above Atlanta.

When I won that ’88 race, I knew that he was as proud as hell of me, as if I was his kid brother. And in a way I surely was.

One day, a few months before he passed, he went into an eloquent chat about the English writer and critic Cyril Connelly. He quoted Connelly as saying, “Inside every fat man there is a thin man wildly signaling to get out.” And then, “Whom the Gods wish to destroy, they first call promising.”

In one of our last talks, Ralph, deep in his cups, told me of how, at the height of the Great Depression, his mother had taken him and his kid brother and sister and put them out at a state orphanage. He remembered the gates closing. He was about seven years old.

“Sometimes I still get the feeling of watching that car pull away from us,” he said. He had never mentioned that before.

Ben Jones is an actor, singer, writer, and recovering politician who lives on a farm in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. His memoir Redneck Boy in the Promised Land was published by Random House. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives as a Congressman from Georgia. He has appeared in countless productions and films, but is surely best known as the affable mechanic “Cooter” on the hit television series The Dukes of Hazzard.